Beatriz Lindemann ’25 and Antonia Pinnar ’25 • February 26, 2024

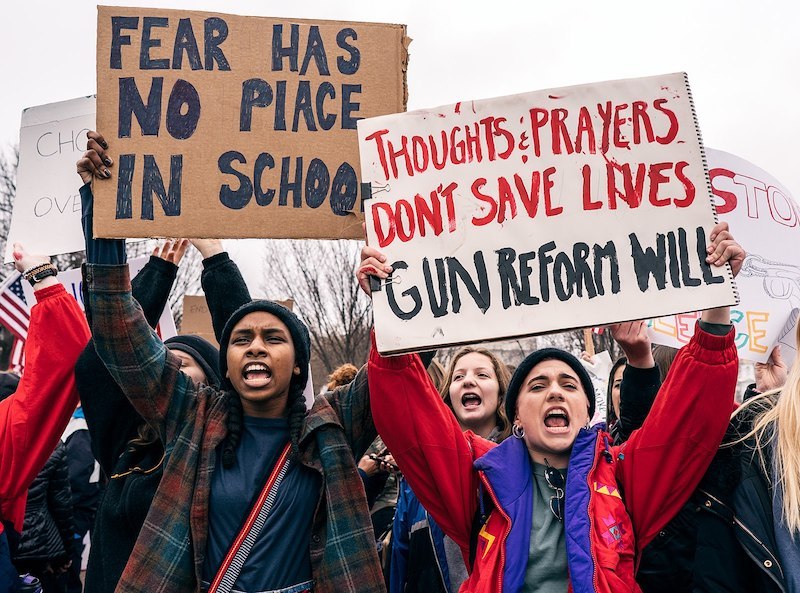

For many years, the ultimate goal of many hard working and competitive high school students was to attend a top 20 university. However, since the October 7th attacks on Israel, many Jewish students no longer feel safe or welcome attending these prestigious institutions. Amidst student complaints about escalating hate, large protests on campuses, and the participation of university professors and staff in contributing to the unsafe atmosphere, the credibility of these universities has been called into question.

Since the start of the ongoing school year, it is reported that 73% of Jewish students have witnessed acts of antisemitism on campus, according to the Anti-Defamation League. Last November, at Harvard University, video footage circulated the media demonstrating pro-Palestine protestors cornering and mobbing a Jewish student. More recently, six Harvard University students have decided to sue their school, arguing that professors contributed to the antisemitic atmosphere on campus.

In December, a congressional hearing provided an opportunity for several top college presidents, including representatives from Harvard University, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the University of Pennsylvania, to address concerns regarding campus circumstances. When questioned about whether “calling for the genocide of Jews violates Harvard’s code of conduct,” former Harvard President Claudine Gay offered a response claiming that the situation is context dependent. In early January, Gay resigned from her position under mounting pressure from groups condemning her inability to condemn hateful rhetoric on campus.

Many students view the inability of their university presidents, who represent the ideologies at the heart of their institutions, to categorize antisemitic speech as “harassment” as a lack of action taken towards fostering an inclusive campus. Following these hearings, questions were raised about these leaders’ commitment to upholding a culture of tolerance at their respective colleges.

When asked about his opinions regarding President Gay’s testimony, Jonas Freeman, a current sophomore at Harvard University, said, “We were all shocked by how technical her responses were and how she failed to acknowledge the reality, when of course calling for the genocide of Jews is completely wrong.” The sophomore explained that “In cases of antisemitism, a student may be harassed to answer for the Israeli government when actually, their only reason for being harassed in the first place is because they were Jewish.”

Audrey Harrelson ’22, a sophomore at Barnard College, mentioned that at a post-October 7th Barnard, “everything in general has felt a lot more divided.” She shared that Columbia University and Barnard students use an online platform to communicate amongst themselves called sidechat. Recently, she said, “the outward hate and antisemitism [on the platform] was something I had never witnessed in my life, and that’s something that was most shocking to me.”

Harrelson also mentioned witnessing antisemitic rhetoric and slogans at the many pro-Palestine protests that have occurred on Columbia and Barnard’s campuses, which have been happening “every three days” since October 7—“and even that’s a conservative estimate.”

Although antisemitism is on the rise on college campuses across the United States, students have reported seeing it more at northern schools than at southern schools. Katie Bernstein, a sophomore at Duke University, said that the months after October 7 have been more defined by a sense of solidarity and community support. “There is a large Jewish population at Duke,” Bernstein said. “People became more in touch with Judaism, not in a religious sense but more in a community sense.”

Similarly, Olivia Rubell ’23, a freshman at Tulane University, said she felt grateful for the atmosphere on campus. “There’s been a stronger sense of Jewish community ever since October 7th. It’s been really difficult, but at school it’s really nice because you feel like you have some sort of community because a lot of us are Jewish. Hillel and Chabad have really stepped up at Tulane, and they are making sure that if students ever need someone to talk to, the doors are always open.”

Even so, Rubell said that while the Tulane community has handled antisemitism better than many other higher education institutions, there have still been incidents of antisemitism on campus. “At school, there was a Pro-Palestine rally that got way out of hand, and one of my friends got hit in the face by some random woman,” she explained. “I also want to note that the Pro Palestine rallies on the Tulane campus are not by students. They are adults who want to incite violence. [The protests] are on the sidewalk where we have to walk to get to class. People don’t feel comfortable walking there anymore.”

What could colleges do better? From Bernstein’s perspective, they should start by acknowledging, and educating students about, the messages of hate behind certain pro-Palestinian slogans. “What colleges could do better is informing students on the situation and explaining why certain phrases, such as ‘From the River to the Sea, Palestine will be free,’ are antisemitic,” Bernstein said. “I think students have a right to voice their opinions, but obviously they should not be calling for the genocide of Jews. That should not be allowed.”

More generally, Bernstein said, “I honestly think that the best way colleges can make a more inclusive environment and combat antisemitism is just to condemn hate of all kinds.”

At many universities, discrimination directed towards most minorities is not tolerated, and yet when there is hate directed towards Jewish people, several institutions seem to have turned a blind eye. These colleges have let their Jewish students down. Failing to condemn antisemitism sets a precedent which allows students to be harassed and hated for simply being Jewish. It is imperative that all forms of hate speech be prohibited in school environments. Picking and choosing which minorities to protect is dangerous and inequitable. While having different opinions builds a diverse community, respecting those different perspectives and rejecting hate will create a healthy community—one that unites all students.

Please read the original article on The Recatalyst.